Below is a long-form, end-to-end technical blog post, written as if for experienced developers who want to truly understand how computers run networked applications. It’s conceptual, precise, and practical, not academic fluff.

From HTTP Requests to CPU Cycles:

A Practical Mental Model of Computer Systems

Modern software often hides the machine behind layers of abstraction: frameworks, runtimes, containers, cloud platforms. This is powerful — but it also creates blind spots.

When performance degrades, latency spikes, or systems fail under load, vague explanations like “the OS handles it” stop being useful.

This article builds a complete mental model of what really happens when software runs — from hardware to kernel to application code — with a particular focus on processes, threads, memory, networking, and I/O.

If you understand this model, you stop guessing and start engineering.

1. Hardware: The Ground Truth

At the lowest level, a computer consists of:

- CPU — executes instructions

- RAM — volatile working memory

- Disk — persistent storage

- Network Interface Card (NIC) — sends and receives packets

Everything else is coordination.

CPU and Cores

A CPU executes instructions sequentially. Modern CPUs have multiple cores, which allows true parallelism.

Important constraint:

One core executes one thread at a time.

No exceptions. Everything else is scheduling.

2. The Operating System: The Mediator

Applications never talk directly to hardware. The kernel mediates access to:

- CPU time

- Memory

- Disk

- Network

Its core job is resource multiplexing: making one machine appear like many.

This is done through three foundational abstractions:

- Processes

- Threads

- Virtual memory

3. Processes: Isolation and Ownership

A process is a running instance of a program.

It provides:

- A private virtual address space

- Ownership of resources (files, sockets)

- Fault isolation

If a process crashes, the kernel cleans up everything it owned.

A process is not execution — it is context.

4. Threads: Execution Units

A thread is the unit that actually runs on the CPU.

Inside a process:

Multiple threads can exist

Threads share memory

Each thread has:

- Its own stack

- Its own registers

- Its own instruction pointer

Key rule:

The CPU schedules threads, not processes.

Processes only matter when switching address spaces.

5. Scheduling and Context Switching

The kernel scheduler decides:

- Which thread runs

- On which core

- For how long

A context switch occurs when:

- One thread stops running

- Another thread resumes

This requires saving and restoring CPU state.

Context switches are not free:

- They flush pipelines

- They disrupt CPU caches

- They add latency

This is why:

- Too many threads hurt performance

- Async/event-driven models exist

6. Memory: Illusion and Reality

Virtual Memory

Each process believes it has a large, continuous memory space.

In reality:

- Memory is fragmented

- Pages may be in RAM or on disk

- The kernel maps virtual → physical addresses

This provides:

- Isolation

- Protection

- Flexibility

But it also introduces:

- Page faults

- TLB misses

- Swapping

Stack vs Heap

Stack

- Per thread

- Function calls, local variables

- Fast, limited

Heap

- Per process

- Shared across threads

- Dynamically allocated

- Managed manually or by a GC

Concurrency bugs live here.

7. Disk and I/O

Disk is orders of magnitude slower than RAM.

The kernel hides this using:

- Page cache

- Read-ahead

- Write-behind buffering

Most “disk reads” are actually RAM reads.

But once you miss cache, latency explodes.

8. Blocking vs Non-Blocking I/O

When a thread performs I/O:

Blocking I/O

- Thread sleeps

- CPU is wasted

- Simple but unscalable

Non-blocking / Async I/O

- Thread continues

- Kernel notifies later

- Scales with fewer threads

This distinction defines modern servers.

9. Networking: From Packets to Processes

The Socket

A socket is a kernel object representing a network endpoint.

It is identified by:

- Protocol (TCP/UDP)

- Local IP

- Local port

- Remote IP (connected sockets)

- Remote port

A socket belongs to a process, not a thread.

TCP Server Lifecycle

socket() → bind() → listen() → accept()

bindassigns an addresslistenputs the socket in passive modeacceptcreates a new socket per client

Important distinction:

A listening socket does not transfer data. Accepted sockets do.

10. DMA: Why the CPU Is Not Copying Your Data

When network data arrives:

- The NIC receives packets

- It uses DMA (Direct Memory Access)

- Data is written directly into RAM

- The CPU is interrupted

Without DMA:

- The CPU would copy every byte

- Throughput would collapse

DMA is essential for:

- High-speed networking

- NVMe SSDs

- GPUs

It also introduces:

- Cache coherency issues

- Security concerns (handled via IOMMU)

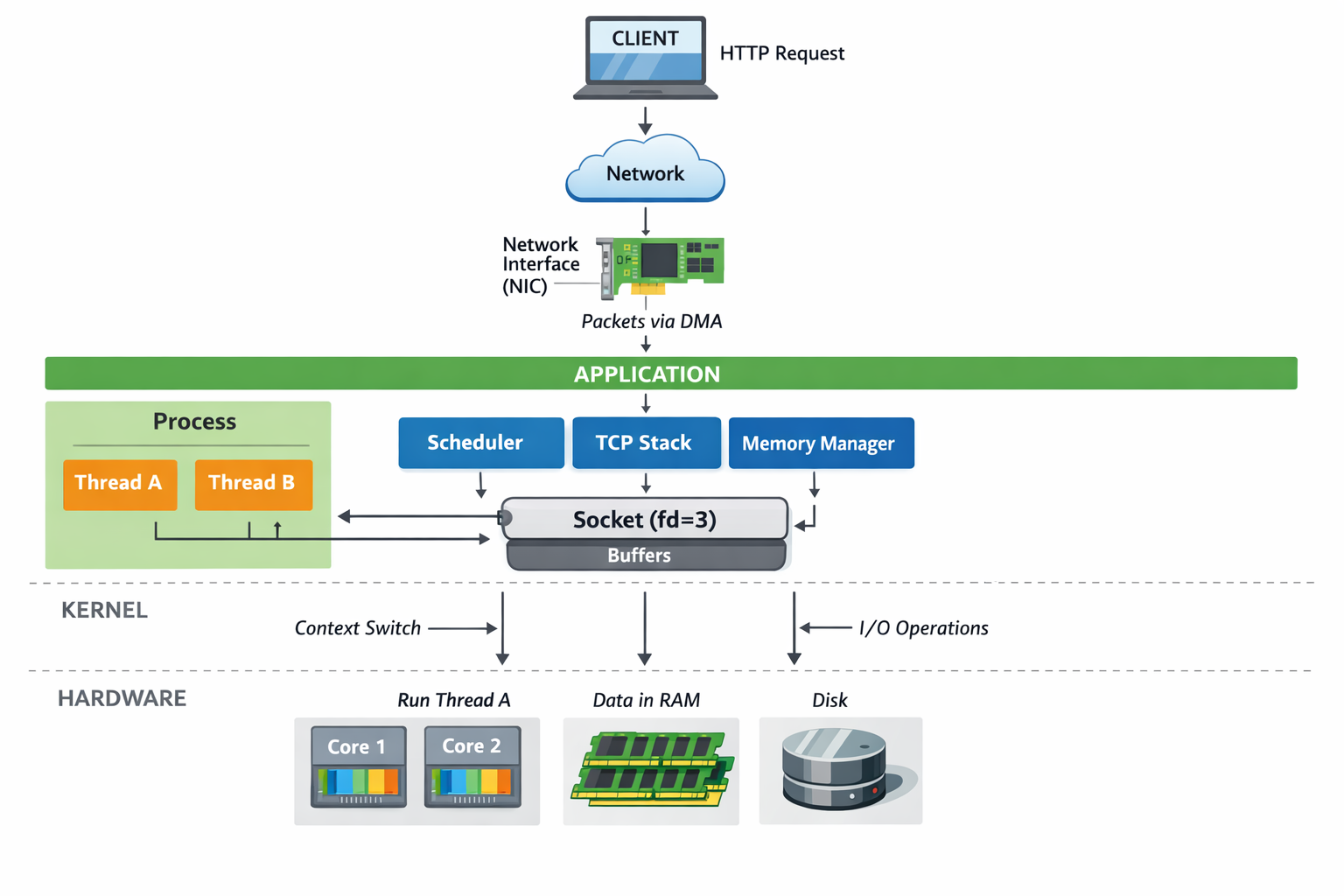

11. A Complete HTTP Request Journey

Putting it all together:

- Client sends TCP packets

- NIC receives data

- DMA copies data into RAM

- Kernel TCP stack processes packets

- Kernel finds the matching socket

- Data is placed in socket buffers

- Kernel wakes a thread from the process

- Scheduler runs the thread on a core

- Application code executes

- Response is written to the socket

- Kernel sends packets via NIC

At every step:

- Memory is involved

- Scheduling decisions are made

- Latency accumulates

12. The JVM as a Case Study

The JVM is not special.

It is:

- A normal process

- With normal threads

- Using normal sockets

- Allocating normal memory

On top of that, it adds:

- A managed heap

- A garbage collector

- A JIT compiler

Java threads map 1:1 to OS threads.

GC pauses are simply:

The kernel scheduling fewer runnable threads because the JVM asked for it.

No magic. Just engineering trade-offs.

13. Common Misconceptions

❌ “More threads = more performance” ❌ “The OS handles that for me” ❌ “Async is faster” ❌ “GC is unpredictable”

Correct versions:

✅ Threads compete for cores ✅ The kernel has costs ✅ Async reduces blocking, not work ✅ GC is deterministic given constraints

14. What This Field Is Actually Called

This topic sits at the intersection of:

- Computer Systems

- Operating Systems

- Systems Programming

- Computer Architecture

- Networking

Canonical references include:

- Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces

- Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective

- UNIX Network Programming

These are not “theoretical” books. They explain why real systems behave the way they do.

15. The Mental Model to Keep

If you remember nothing else, remember this:

Threads execute on cores. Processes own memory and resources. The kernel schedules and mediates. Hardware moves data.

Once you see systems this way:

- Performance problems become explainable

- Design decisions become clearer

- Trade-offs stop being mysterious

Final Thought

Abstractions are powerful — but only if you know what they abstract away.